When society is oppressed, they find a way to resist it, may it be a violent way or an artistic way. Euro guro genre and the subsequent movement, ero guro nansensu, comes under the latter category. The genre was limited, perused by only a set percentage of people.

However, it soon transformed into a social movement as a response to the suffocating cultural complexities of the times. It provided a way for people to express their dissatisfaction with the state of affairs with provocative means. Ero guro nansensu is an artistic rebellion, holding a mirror for society’s anxieties, hidden desires and fears.

The Japanese Eras and their Influence on Ero Guro

To understand why Ero Guro started, it is crucial to understand the historical climate of Japan in the early 20th century. The Meiji era (1868-1912) was marked by Japan’s transformation from being a feudal society to an imperial authority. It underwent rapid modernisation, with the country adopting Western values and cultural elements. This change also prompted an unfortunate decline in the demand for Japanese art in the country itself.

As a result, the succeeding Taisho period (1912-1926) was rich with Western influence that bulldozed its way into traditional art. There was a shift in the country’s political atmosphere, which prompted the era to be called Taisho Democracy, marked by liberalism. Cultural creativity flourished, the artistic and literary works challenging traditionality and venturing in new directions.

However, the Showa period (1926-1989) shifted the culturally vibrant country into militarism and nationalism. This military leadership was even strengthened after the February 26 incident, where a faction of rebel military officers rebelled against the Japanese government. The incident left deep scars on Japanese society, resulting in heightened surveillance, restrictions, and heightened anxiety.

The sudden political and societal changes perpetuated chaos and a sense of rebellion, making people resort to art and literature to express their emotions. As a result, the books, news, music, and art of this era explored fantasy, the unconscious, and abnormality with no hesitation.

All these expressions culminated in the birth of Ero Guro Nansensu, whose presence especially boomed during the Great Depression (1929). People found a way to escape their morbid reality by entering a world of bizarre, grotesque, and erotic narratives. It was the start of a movement that lasted till the mid-1930s. Though, as is evident, the seeds of the genre were sowed during the Meiji and Taisho eras.

- The Sada Abe Incident

The Sada Abe incident is the blend of everything this artistic genre stands for, but which happened in the flesh, in real life. It refers to the murder of Kichizō Ishida at the hands of Sada Abe, a Japanese geisha, prostitute, and his lover. But the story isn’t as simple as that; Sada Abe not only killed him but also castrated his corpse and went hiding with his body parts. Her disappearance lasted three days before she was found by the police.

Such a heinous crime garnered national attention, which brought chaos all over the society. Many reported (false) sightings to the police, one of which caused a stampede, and consequently, a large traffic jam. After she was caught, the reasoning behind her actions was simple: “I loved him so much, I wanted him all to myself… I knew that if I killed him no other woman could ever touch him again, so I killed him…”

The murder, done out of love instead of jealousy, was a sensational scandal for the people. They welcomed it with open arms, as it provided everyone with a distraction from the frenzy following the February 26 incident. Many similar cases took over the nation’s landscape, including Mutsuo Toi’s revenge serial killing spree. Yet, the Sada Abe incident stands out, deemed the quintessential description of the ero guro nansensu movement.

Her confession and the records of her interrogation transformed into a national bestseller in the same year. She was deemed as the dokufu or poison woman, a popular stereotype of transgressive females popularised in the 1870s. This brought forth confessional autobiographies from many female criminals, including Kanno Suga and Fumiko Kaneko.

The Movement and Its Effect on Literature

The Empire of Japan, through the Home Ministry Police Affairs Bureau, monitored and censored all major publications. The rules of this censorship were not easy to parse, and hence publishing ero guro literature became an issue. To remedy this, publishers in the 1920s started publishing novels under the private perusal category. The publishers would pre-censor these books to devoid them of words that would put them under the government’s radar for indecency.

However, the tactic failed, and the publishing industry fought against the oppressive censorship, which led to the abolition of private perusal. It was during the peak of Taisho democracy when enpon, which literally translates to one-yen books, became synonymous with ero guro books. The practice, popularised by the publisher of Kaizō, a Japanese magazine, was picked by all publishers soon enough.

What followed was a wave of ero guro nansensu literature that was accessible to the Japanese society at an affordable rate. However, since these books were ‘banned’, this literature garnered the label of underground, available only through secret buying clubs. Measures were taken to escape the censorship, including adding a table of omitted or censored words in the books. Another tactic was to print limited copies of the books, some of which would be set aside for review. This way, the authorities deeming the content unsuitable for release didn’t cause a problem.

Censorship was made even more intense during World War II when the publishers who advocated the movement lost their rebellious streak. But the literature made its comeback in the post-war period, in turn making the atmosphere of the Showa era liberal.

Ero guro nansensu literature is now free from any governmental inspection. In fact, the National Diet Library has already published the banned literature as a part of its online digital collection.

- Edogawa Ranpo

Tarō Hirai was 29 when he published a story, The Two-Sen Copper Coin, after spending years working odd jobs. He adopted the pen name Edogawa Ranpo, a pseudonym that sounds like Edgar Allan Poe, writing about sleuthing and solving unsolvable cases.

During the 1930s, he took it upon himself to add the themes of bizarre and macabre in his writings. These books sold quickly among the public, allowing him to pursue the genre and give it his own twist. But his works also faced heavy censorship, especially during World War II. While the country engaged in the war, he fought his battle by publishing under different pseudonyms to escape scrutiny.

The post-war era saw Ranpo dedicating himself to promoting mystery fiction in Japanese society. He churned out essays, articles, as well as novels on his beloved fictional private detective. Most of his works were picked for film adaptations, which became a common practice after his death.

Edogawa Ranpo started off as a mystery fiction writer. But, unbeknownst to him, he became one of the literary pioneers of ero guro nansensu.

The Elements of Ero Guro Literature

Ero guro literature is rich with the themes of erotic, grotesque, and nonsense. But apart from that, the books of this genre also explore many other elements, which are:

- Eroticism: Eroticism is an integral part of this genre, delving into sexual themes. These may range from mild eroticism to explicitly fetish-riddled narrative. However, it is not equal to pornography, as the former has an artistic or social motive, while the latter is concerned with sexual pleasure.

- Grotesque: Ero guro books showcase a disturbingly obsessive fascination with macabre, often showcased in the form of murder, mutilation, and decay. The graphic details of these may be repulsive for the ones who are not used to such themes. When combined with eroticism, the books become a way to unsettle your mind through a graphic plot.

- Absurdity: Most of the works of this genre also enters the world of absurdity and surrealism, catering to the nansensu part of the movement. As a result, books may feature dreamlike scenes, supernatural elements, and illogical sequences that stray far from conventional norms of reality.

- Social commentary: Ero guro books are meant to give you the shock after reading something sexually and horrifyingly charged. However, it is widely used as a handy tool for social commentary, criticising taboos, traditional norms, and hypocrisy during its presence in Japan.

- Psychological exploration: Many literary works of this movement offer a deep dive into the dark side of the human psyche. As a result, there is a fascinating exploration of themes like obsession, madness, and fascination with gory things through its characters. This psychological aspect adds more to the unsettling atmosphere of not only the genre but the general movement as well.

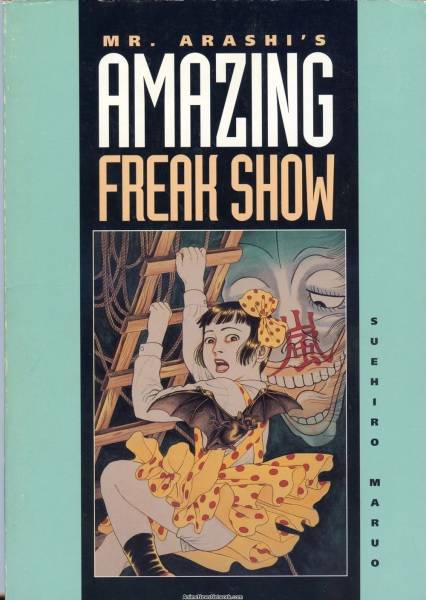

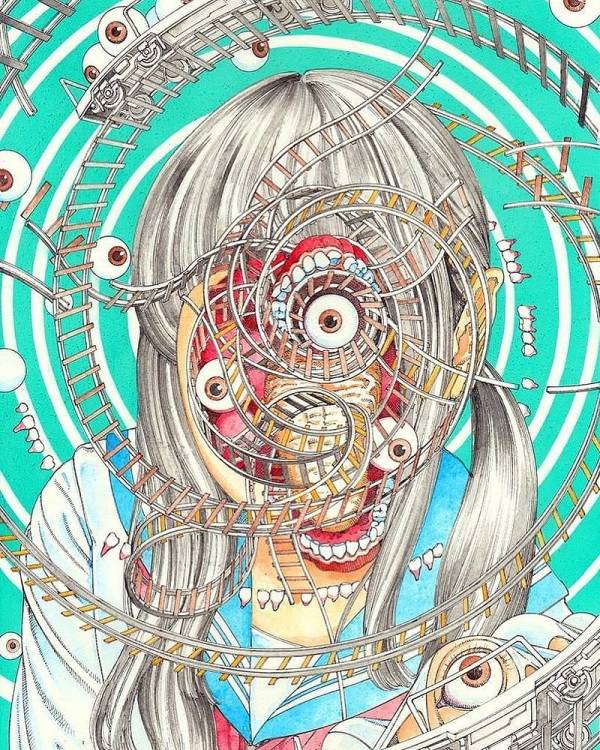

All these elements come together to lay out a base that is as unsettling as the plot idea itself. It is evident in books like Fraction (Shintaro Kago), Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show (Suehiro Maruo), and Strange Tale of Panorama Island (Edogawa Ranpo).

What is the Influence of Ero Guro Nansensu Today?

Ero guro nansensu waned, like any other movement, in the later part of the 20th century. However, its essence meandered through the dark and the underground, solidifying its subtle presence for the decades to come.

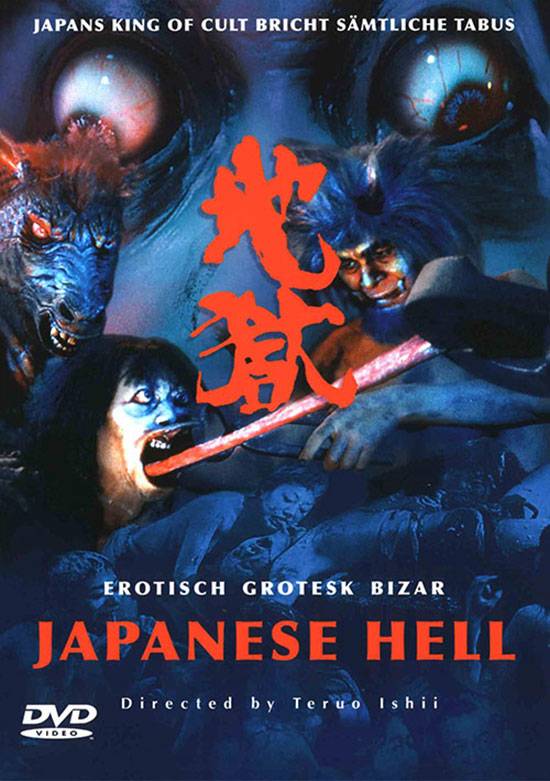

The first and foremost evident influence is on the art and media. Manga artists such as Shintaro Kago and Suehiro Maruo write deeply unsettling stories that lure you into exploring the darker themes. Whereas filmmakers like Teruo Ishii and Sion Sono don’t hesitate to add ero guro elements in their films. Japanese music, especially by rock and visual kei bands, often touches on themes of eroticism, psychological distress, and death. Ero guro’s gory hands have also clawed their way into the tattoo industry. As a result, you will find many disruptive designs that resonate with what the ero guro nansensu movement represented.

One may refer to the echoes of ero guro nansensu in the 21st century as the seedy underbelly of the literary world. It allows people to embrace the decadent and hedonistic side of the human psyche while fostering the contempt of societal norms.